The Stock Market Typically Bottoms Before the End of a Fed Rate-Hike Cycle. Here’s How to Make That Bet Pay Off

What to expect when you’re expecting the Fed to pivot

A lot of money can be made betting on when the Federal Reserve will “pivot” – that is, take its foot at least partially off the rate-hike gas pedal. Yet a lot of money can also be lost, as we saw on August 26 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.96% lost more than 1,000 points after Fed Chair Jerome Powell dashed hopes that the Fed’s pivot had begun in July.

So it’s helpful to review past rate-hike cycles to see how investors fared when trying to anticipate when those cycles came to an end.

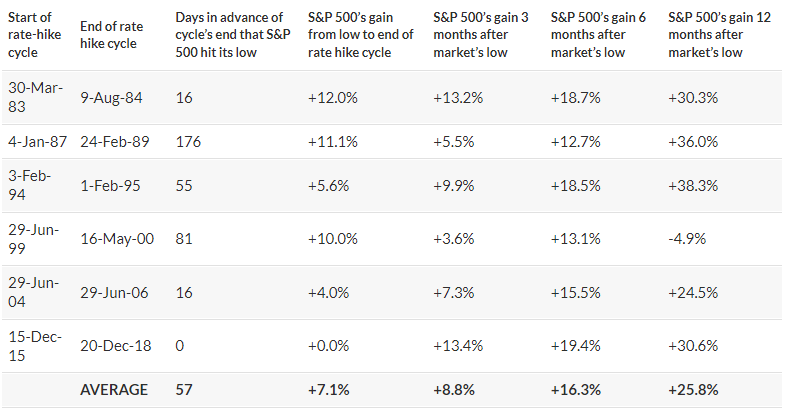

To do that, I focused on the six distinct rate-hike cycles since the Fed began specifically targeting the Fed funds rate. The table below reports how many days prior to the end of those cycles that the stock market hit its low. (Specifically, I focused on a six-month window prior to the end of each cycle, and determined when within that window the S&P 500 SPX, -1.10% hit its low.)

As you can see, the market hit its low an average of 57 days prior to the end of the Fed’s rate-hike cycle – about two months. Yet notice also that there is quite a range, from no lead time at one extreme to almost the entire six-month window on which I focused. Given that it’s hard to know when the Fed will actually begin to pivot, this wide range illustrates the uncertainty and risk associated with trying to reinvest in stocks in anticipation of a pivot.

Nevertheless, the table also shows that there are hefty gains to be had if you get it even partially right. For example, the S&P 500 gained an average of 7.1% over the period between the market’s pre-pivot low and the actual end of the rate-hike cycle. That’s an impressive return for a two-month period. Furthermore, the average gain over the six months following the pre-pivot low is a strong 16.3%, and over the 12 months following that low it is 25.8%.

How should you play this high-risk/high-reward situation? One way is to dollar-cost average up to whatever is your desired equity exposure. For example, you could divide into five tranches the total amount you want to eventually put back into the stock market, and invest each tranche in equities at the end of the next five calendar quarters. If you followed this approach – and it is just one of many possible ones – you’d be back to your target equity exposure by the beginning of 2024.

Such an approach won’t get you into stocks at the exact pre-pivot low, but hoping for that is a delusion. Yet the approach should get you an average buy-in price that is better than waiting. It should also protect you from days like August 26, when the market punished those who bet that the Fed had already started to pivot.